Generational GC

This document discusses the internals of SGen. If you are interested on how to use SGen and how to tune it for your own application workloads, see the document Working With SGen.

For a few releases, Mono has shipped with a new garbage collector, we call this the SGen garbage collector. This garbage collector can be enabled by passing the –gc=sgen flag to Mono or if you are embedding Mono, by linking against the libmonosgen library instead of the libmono library.

The Benchmark Suite continuously runs benchmarks for each Mono revision to track performance regressions using MonkeyWrench. The data is automatically collected and processed on this page: http://wrench.mono-project.com/gcbench/.

On MacOS X SGen provides several DTrace probes, described in the document SGen DTrace.

Garbage Collection

The garbage collector, in short, is that part of the language’s or platform’s runtime that keeps a program from exhausting the computer’s memory, despite the lack of an explicit way to free objects that have been allocated. It does that by discovering which objects might still be reached by the program and getting rid of the rest. It considers as reachable objects those that are directly or indirectly referenced by the so-called “roots”, which are global variables, local variables on the stacks or in registers and other references explicitly registered as roots. In other words, all those objects are considered reachable, as well as those that they reference, and those that they reference, and so on.

Here are some of its features:

- Two generations.

- Multi-threaded

- Mostly precise scanning (stacks and registers are scanned conservatively).

- Upcoming versions of Mono remove this limitation, see the Precise Stack Marking section for more information.

- Two major collectors:

- Copying for nursery/minor collections

- Mark and Sweet for the old generation and major collector

- Per-thread fragments for fast per-thread allocation.

- Uses write barriers to minimize the work done on minor collections.

- Multi-core garbage collection

- Stop the world, meaning that during garbage collection, the program is stopped.

SGen-GC manages memory in four groups:

- The nursery, where new small objects are allocated.

- Large object store, where large objects are allocated.

- Old generations, where small objects are copied to.

- Pinned chunks, for objects that have been pinned-allocated.

The garbage collector will trigger a collection when there is no space anymore in the memory already requested from the operating system. The collector distinguishes between two kinds of collections: major collections and nursery-collections which only operate on the current nursery.

The principle behind this two-stage collection (major and nursery) is based on the observation that many programs create a lot of short-lived objects that can be quickly collected. All new objects are allocated in the nursery and during a collection the surviving objects are moved to the older generation memory block. Nursery collections reduce the amount of work required by the collector because usually there are few surviving objects that need to be copied, leaving lots of free space for subsequent allocations.

When the nursery is full, the collector will trigger a nursery collection, this is performed by the copying GC. When the old generation is full as well, a major collection is performed.

The garbage collector is complicated by a number of issues:

- Must work with multi-threaded applications.

- The collection can be triggered by any thread.

- We need to track which objects are pinned, as we can not move those objects.

- Large objects are too expensive to move, so they are dealt with separately using a mark/sweep during a major collection.

- Some kinds of objects can not be moved either (interned strings, type handles) and are also dealt with using mark/sweep.

Before doing a collection (minor or major), the collector must stop all running threads so that it can have a stable view of the current state of the heap, without the other threads changing it.

The following section describes the basics of Garbage Collection in Mono: Copying Collection and the Mark and Sweep Collector.

Copying Collection

Mono uses different strategies to perform garbage collection on the new generation (what we call the nursery) and the old generations.

Copying collection is used for the minor colletions in the nursery.

A copying garbage collector improves data locality and helps reducing the memory fragmentation of long-running applications or applications whose allocation patterns might lead to memory fragmentation in non-moving collectors.

The copying major collector is a very simple copying garbage collector. Instead of using one big consecutive region of memory, however, it uses fixed-size blocks (of 128 KB) that are allocated and freed on demand. Within those blocks allocation is done by pointer bumping

Mono has historically used the Boehm-Demers-Wiser Conservative Garbage Collector which provides a very simple and non-intrusive interface for providing applications with garbage collection.

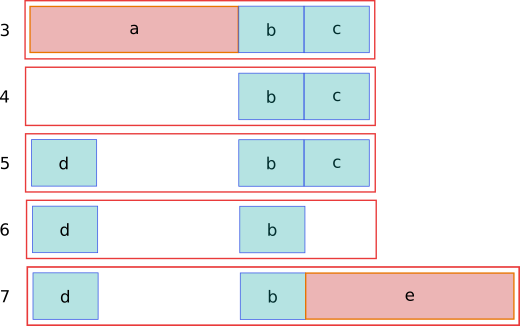

Fragmentation of the heap is a common problem faced by C and C++ applications and it happens under certain allocation patterns that sometimes are outside the developer control. For example, consider the following allocation pattern:

- Allocate an object which is 4096 bytes long (a).

- Allocate an object which is 1024 bytes long (b).

- Allocate an object which is 1024 bytes long (c).

- Release (a)

- Allocate another 1024 byte sized object (d).

- Release (c)

- Allocate an object which is 4096 long. (e).

Here is how the heap would look like during each step, notice that although there are 4096 bytes available to allocate, the memory is not contiguous and the heap has to be extended.

Some memory allocators are able to return the “holes” back to the operating system if these holes happen to match the operating system minimum allocation sizes. For most collectors, the complication is that these holes can be created due to smaller allocations in the address space.

A compacting collector would be able to move the data and not grow the heap:

This represents an ideal situation, but there are some cases when moving the objects is not possible. In the CIL universe this can be caused because objects have been “pinned” which prevent objects from being moved. Pinning can happen either explicitly, (when you use the “fixed” directive in C# for example, or implicitly as Mono’s SGen collector treats the contents of the stack conservatively.

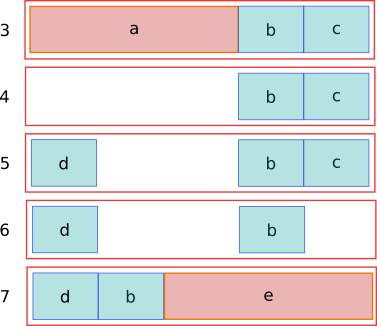

At a major collection all objects for which this is possible are copied to newly allocated blocks. Pinned objects clearly cannot be copied, so they stay in place. All blocks that have been vacated completely are freed. In the ones that still contain pinned objects we zero the regions that are now empty. We don’t actually reuse that space in those blocks but just keep them around until all their objects have become unpinned. This is clearly an area where things can be improved.

Nursery Collection

The nursery is the generation where objects are initially. In SGen, it is a contiguous region of memory that is allocated on starts up, and it does not change size. The default size is 4 MB, but a different size can be specified via the environment variable MONO_GC_PARAMS when invoking Mono. See the man page for details or Working with SGen.

Allocation

In a classic semi-space collector allocation is done in a linear fashion by pointer bumping, i.e. simply incrementing the pointer that indicates the start of the current semi-space’s region that is still unused by the amount of memory that is required for the new object.

In a multi-threaded environment like Mono using a single pointer would introduce additional costs because we would have to do at least a compare-and-swap to increment it, potentially looping because it might fail due to contention. The standard solution to this problem is to give each thread a little piece of the nursery exclusively from which it can bump-allocate without contention. Synchronization is only needed when a thread has filled up its piece and needs a new one, which should be far less frequent. These pieces of nursery are called “thread local allocation buffers”, or “TLABs” for short.

TLABs are assigned to threads lazily. The relevant pointers, most notably the “bumper” and the address of the TLAB’s end, are stored in thread local variables. Currently TLABs are fixed in size to 4 KB (actually that’s the maximum size – they might be smaller because the nursery can be fragmented). In the future we might dynamically adapt that size to the current situation. The less threads that are allocating objects, the larger the TLABs should be so that they need to be assigned less often. On the other hand, the more threads we allocate TLABs to the sooner we run out of nursery space, so we will collect prematurely. In that situation the TLABs should be smaller. Ideally a thread should get a TLAB whose size is proportional to its rate of allocation.

Calling from managed into unmanaged code involves doing a relatively costly transition. To avoid this the fast paths of the allocation functions are managed code. They only handle allocation from the TLAB. If the thread does not have a TLAB assigned yet or it is not of sufficient size to fulfill the allocation request we call the full, unmanaged allocation function.

Collection

Collecting the nursery is not much different in principle from collecting the major heap, so much of what is discussed here also applies there

Coloring

The collection process can be thought of as a coloring game. At the start of the collection all objects start out as white. First the collector goes through all the roots and marks those gray, signifying that they are reachable but their contents have not been processed yet. Each gray object is then scanned for further references. The objects found during that scanning are also colored gray if they are still white. When the collector has finished scanning a gray object it paints it black, meaning that object is reachable and fully processed. This is repeated until there are no gray objects left, at which point all white objects are known not to be reachable and can be disposed of whereas all black objects must be considered reachable.

One of the central data structures in this process, then, is the “gray set”, i.e. the set of all gray objects. In SGen it is implemented as a stack.

The Roots

The collection process can be thought of as a coloring game. At the start of the collection all objects start out as white. First the collector goes through all the roots and marks those gray, signifying that they are reachable but their contents have not been processed yet. Each gray object is then scanned for further references. The objects found during that scanning are also colored gray if they are still white. When the collector has finished scanning a gray object it paints it black, meaning that object is reachable and fully processed. This is repeated until there are no gray objects left, at which point all white objects are known not to be reachable and can be disposed of whereas all black objects must be considered reachable.

One of the central data structures in this process, then, is the “gray set”, i.e. the set of all gray objects. In SGen it is implemented as a stack.

Forwarding

In a copying collector like SGen’s nursery collector, which copies reachable objects from the nursery to the major heap, coloring an object also implies copying it, which in turn requires that all references to it must be updated. To that end we must keep track of where each object has been copied to. The easiest way to do this is to use a forwarding pointer. In Mono, the first pointer-sized word of each object is a pointer to the object’s vtable, which is aligned to at least 4 bytes. This alignment leaves the two least significant bits for SGen to play with during a collection, so we use one of them to indicate whether that particular object is forwarded, i.e. has already been copied to the major heap. If it is set, the rest of the word doesn’t actually point to the vtable anymore, but to the object’s new location on the major heap. The second bit is used for pinning, which I will discuss further down.

The Loop

Here is a simplified (pinning is not handled) pseudo-code implementation of the central loop for the nursery collector:

1: while (!gray_stack_is_empty ()) {

2: object = gray_stack_pop ();

3: foreach (refp in object) {

4: old = *refp;

5: if (!ptr_in_nursery (old))

6: continue;

7: if (object_is_forwarded (old)) {

8: new = forwarding_destination (old);

9: } else {

10: new = major_alloc (object_size (old));

11: copy_object (new, old);

12: forwarding_set (old, new);

13: gray_stack_push (new);

14: }

15: *refp = new;

16: }

17: }

In line 2 we pop an object out of the gray stack and in line 3 we loop over all the references that it contains. refp is a pointer to the reference we’re currently looking at. In line 4 we fetch the actual reference. We are only interested in collecting the nursery, so if the reference already points to the old generation we skip it (lines 5 and 6). If the object is already forwarded (line 7) we fetch its new location (line 8). Otherwise we must copy it to the major heap. To that end we allocate the space required (line 10), do the actual copying (line 11) and forward the object (line 12). That newly copied object must also be processed, so we push it on the gray stack (line 13). Finally, for both cases, we update the reference to point to the new location of the object (line 15).

Since the purpose of a nursery collection is to avoid scanning all the allocated memory, the collector and the VM keep track of any pointers that have changed in the old generations which might point to objects in the nursery (as this would determine objects that must be kept alive as well). These changes are known as the remembered set.

Pinning

Either because the programmer has manually pinned an object (by using the fixed statement in C#) or because we implicitly pinned an object because it is referenced in a managed to unmanaged transition or because the platform does not support precise stack scanning some object might be pinned down in memory.

Pinned objects are a bit of a complication since it is not possible to completely clean out the nursery, so it can become fragmented. This also requires an additional check in the central loop.

Finishing Up

After all the copying is done what’s left is to clean up the nursery for the next round of allocations. SGen doesn’t actually zero the nursery memory at this point, however. Instead that happens at the point when TLABs areassigned to threads. The advantage is not only that it potentially gets distributed over more than one thread, but also that is has better cache behavior – the TLAB is likely to be touched again soon by that thread.

What has to happen at this point, though, is to take score of the regions of nursery memory that are available for allocation, which means everything apart from pinned objects. Since we have a list of all pinned objects this is done very efficiently. It is these “fragments” from which TLABs will be assigned in the next mutator round.

Large Objects

SGen-GC also handles large objects in a special way. Since moving large objects is an expensive operation that can easily hurt performance. The SGen-GC allocates large objects directly on pages managed by the operating system, this allows the collector to release the memory back to the operating system when those blocks are no longer in use.

Implementation Details

Note: This is an evolving piece of SGen-GC.

Managing these objects differently can fragment the continuity of the address space, but since the memory is returned to the operating system the memory usage pattern is different than an allocator that would mix large and small allocations as these large objects are always allocated independently.

This reflects SGen-GC strategy as of May 29th, 2006, but it is an area that we will tune to reflect usage scenarios of Mono applications and will likely change to take into consideration the age of the large objects and possible perform copying/moving to a special Large Object section at some point.

Mark And Sweep Collector

In contrast to the copying collector a mark-and-sweep collector has to deal with individual objects being freed and new objects filling up that space again. (This is different from pinned objects leaving holes in blocks for the copying collector because in that case it is expected that there will only be a tiny number of remaining pinned objects, so the free regions will be large, whereas here it is expected that many objects survive, leaving lots of small holes). This creates the problem of fragmentation – lots of small holes between objects that cannot be filled anymore, resulting in lots of wasted space.

Blocks

The basic idea of SGen’s Mark-and-Sweep collector is to have fixed-size blocks, each of which is divided into equally sized object slots of a variety of different sizes – this is similar to what Boehm does. One advantage of this over allocating objects sequentially is that the holes are always the same size, so if there are new objects arriving at that size the holes can always be filled.

Of course it is not feasible to support blocks with slots of every conceivable object size, so we space out the different supported sizes so as not to waste too much space (in the future we might want to choose the sizes dynamically, to fit the workload). Another thing that works to our advantage is that, since the slots have a known size, we don’t have to keep tabs on where they start and end. All we need is one mark bit per object which we keep in a separate region for better memory locality (we could use unused bits in the first object word, like the nursery collector does). For faster processing we’re actually keeping one bit per potential object start address, i.e. 1 bit per 8 bytes.

Since we only have a limited number of different slot sizes, we can also keep free lists, so allocation is more efficient because it doesn’t involve search.

During garbage collection it is necessary to get from an object to its block in order to access its mark bit. The size of each block is 16 KB, and they are allocated on 16 KB boundaries, so to get from an object that is inside a block to the address of its containing block a simple logical AND is sufficient. Unfortunately, large objects live outside of blocks and for them this operation would yield a bogus block address. To determine whether an object is large we need to examine its class metadata which is referenced from its VTable, requiring three loads (the “fixed heap” variant of the collector solves this problem and is described below.)

Each block has a “block info” data structure that contains metadata about the block. Apart from the size of the object slots and several other pieces of data it also contains the mark bits.

Fixed Heap

In the standard Mark-and-Sweep collector the blocks are allocated on demand, so they are potentially scattered all over the process’s address space. The fixed heap variant, on the other hand, allocates (using mmap) a heap of a fixed size (excluding the large object space) on startup and then assigns blocks out of that space. The advantage here is that we can check whether a pointer is within a block simply by checking whether it falls within the bounds of the allocated space, so no loads are necessary to get to its mark bit.

In standard Mark-and-Sweep the first word of each block links to its block info. Fixed heap can forego this load as well because the block infos are also allocated sequentially, so all that is needed to get to a block info is its index which is the same as its block’s index, which can be determined from the block address.

The obvious disadvantage of fixed heap Mark-and-Sweep is that the heap cannot grow beyond its fixed size. On some workloads fixed heap yields significant performance improvements. I will try to give some benchmarking results in a later post.

Non-Reference Objects

Objects that don’t contain references don’t have to be scanned, which implies that they also don’t have to be put on the gray stack. To handle this special case more efficiently Mark-and-Sweep uses separate blocks for objects with versus without references. The block info contains a flag that says which type the block is.

For the fixed heap collector this separation means that we don’t even have to load a single word of an object or its metadata if it doesn’t contain references

Evacuation

Even despite the segregation of blocks according to fixed object sizes one form of memory waste can still occur. If the workload shifts from having lots of objects of a specific size to having only a few of them, a lot of blocks for that object size will have very low occupancy – perhaps a single object will still be live in the block and no new objects will arrive to fill the empty slots.

Unlike Boehm, SGen has the liberty to move objects around. During the sweep stage of a collection we keep statistics on the occupancy of blocks of all slot sizes. If the occupancy for a given slot size falls below a certain (user definable) threshold then we mark that slot size for evacuation on the next major collection.

When blocks of a slot size are being evacuated Mark-and-Sweep acts like a copying collector on the objects within those blocks. Instead of marking them they are copied to newly allocated blocks, filling them sequentially and emptying all the sparsely occupied ones which will then be freed during the following sweep.

Blocks with pinned objects are exempt from this whole process since they cannot be freed anyway.

Note that the occupancy situation might change between a sweep and the following major collection – the workload could change in the mean time and produce lots of live objects of that size which would all be copied, without actually saving any space. SGen cannot tell which objects will be live without doing the mark phase because that’s the mark phase’s job, so we take the risk of that happening.

As a side-note: Sun’s Garbage-First collector solves this problem by running the mark phase concurrently with the mutator, so it is actually able to tell at the start of a garbage collection pause which blocks will contain mostly garbage.

Parallel Mark

The mark phase can be parallelized with reasonable effort. Essentially, a number of threads each start with a set of root objects independently. Each thread has its own gray stack, but care must be taken that work is not repeated. Two threads can compete for marking the same object, and if they both put the object into their gray stacks, the object will be scanned twice, which is to be avoided.

Some care must also be taken with handling objects that still reside in the nursery. They have to be copied to the major heap and a forwarding pointer must be installed. The forwarding pointer can only be installed after the space on the major heap has been allocated (otherwise where would it point to?), so two threads might do that independently but only one will win out and the other will have done the allocation in vain.

It is not actually sufficient to just partition the set of root objects between the worker threads – some threads might end up having a far smaller share of the live object graph to work with. SGen currently uses a shared gray stack section buffer where worker threads deposit parts of their gray queues for the others to take.

Parallel mark achieves quite impressive performance gains on some workloads, but on most the gains are still somewhat disappointing. I suspect the work distribution needs improvement.

Concurrent Sweeps

The sweep phase goes through all blocks in the system, resets the mark bits, zeroes the object slots that were freed and rebuilds the free lists.

None of those data structures are actually needed until the next nursery collection, so the sweep lends itself to be done in the background while the mutator is running, which is what Mark-and-Sweep can do optionally. The next nursery collection will in that case wait for the sweep thread to finish until it proceeds.

Internal mono GC interface

The GC exposes two interfaces, a public interface which is limited to a few methods in the metadata/mono-gc.h header file.

And a more extensive internal interface consumed by the JIT engine, this one is declared in metadata/gc-internal.h

This GC is also different from the Boehm GC in the fact that only objects are GC-tracked: it is not possible to allocate blobs of memory and have them collected by the GC.

The entry points for allocating objects are:

void *mono_gc_alloc_obj (MonoVTable *vtable, size_t size);

void *mono_gc_alloc_pinned_obj (MonoVTable *vtable, size_t size);

mono_gc_alloc_pinned_obj must be used for objects that can’t be moved in memory (like interned strings).

The GC also provides the following convenience function to allocate memory and register the area as a root with a specified GC descriptor. This block of memory must be explicitly freed with a call to mono_gc_free_fixed().

void *mono_gc_alloc_fixed (size_t size, void *descr);

mono_gc_alloc_obj is used from within the Mono runtime through the following macros: ALLOC_PTRFREE, ALLOC_OBJECT, ALLOC_TYPED.

Collection

Major Collection

Major collections look at all the objects allocated by the application: they look at the old generations and the nursery. In addition to performing the copying and compacting of most objects, a mark/sweep is performed for pinned chunks and for large objects as well.

During a major collection, the following steps take place:

- Pinned objects (implicit and explicit) are identified and flagged.

- A new section of memory for the generation is allocated.

- Pinned objects are scanned for references to other objects.

- All roots are traversed and scanned for references to other objects.

- Objects referenced by the roots and pinned objects are now copied

- Sweep of large objects is performed.

- Sweep of pinned objects is performed.

- Any unused sections are released.

- Nursery fragments are reconstructed.

The various stages are described in more detail in the following sections.

Stopping the world.

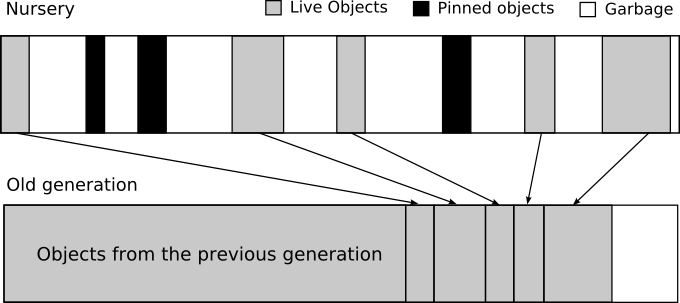

To perform the garbage collection, it is important that all the running threads are stopped, this is called “stopping the world”. This guarantees that no changes are happening behind the GC’s back and also, the compacting collector will need to move the objects, and update all pointers to the objects to point to their new locations.

The dark grey areas are scanned conservatively

Stopping threads and resuming execution is done by the stop_world() and restart_world() routines, which are invoked before a major collection or a nursery collection are performed.

To actually implement the stop and restore, a couple of Unix signals are used: one signal is used to to notify a thread that it should stop, and another is used to notify a thread that it can resume execution. These signals are setup when the GC is initialized.

Stopping is done by calling the thread_handshake routine, which sends the stop signal to all known threads (using pthread_kill). The signal handler for the thread will in turn sleep until a signal is received to resume execution.

The Mono runtime will automatically register all threads that are created from the managed world with the garbage collector. For developers embedding Mono it is important that they register with the runtime any additional thread they create that manipulates managed objects with mono_thread_attach.

The information about each registered thread is tracked in the thread_table hash table, a hash table that contains nodes of type SgenThreadInfo. The SgenThreadInfo contains among other things the RememberedSet for the thread as well as the end of the stack.

Another important side effect of suspending the threads with a signal handler is that the values held on the registers are stored on the stack of each thread. The signal handler will update the stack_start value in the current thread information. The GC will use this to conservatively scan the memory between stack_start and stack_end.

The dark areas represent the blocks of memory that the SgenThreadInfo will track for each thread in the running application and contain the live data on each of the thread stacks, in addition to the register values.

On some operating systems like OSX and Windows, a different mechanism is used to stop the threads (typically with a native call that suspends the threads).

Roots

Roots are the initial set of object references from which all of the other objects in a program are referenced. These root object references are made up of all static field references, CPU registers referencing objects, variables stored on all of the thread stacks, and any internal object references that the runtime holds.

Objects that are no longer reachable from the roots are garbage collected.

The dark regions are the root objects, the gray regions are the objects that are referenced by any root objects or other referenced objects and the white regions represent the garbage.

Internally, the collector tracks two kinds of records, conservative root records and precise root records.

Both records are created through the mono_gc_register_root, its prototype is:

int mono_gc_register_root (char *start, size_t size, void *descr)

The start and size arguments are used to specify the block in memory that represents the root.

The descr argument is a root descriptor used to specify the contents of the block. The ROOT_DESC_CONSERVATIVE descriptor (which happens to be NULL) means that the block will be scanned conservatively for roots. Otherwise the descr represents a descriptor that specifies the object references in the specified block.

Currently the stack and register contents are scanned conservatively (the CPU registers are copied into a small buffer of memory that has been registered as a root block of memory that is to be scanned conservatively).

The collector tracks each of these registered roots in the roots_hash hash table, a hash table that contains node of type RootRecord. Each RootRecord tracks a block of memory (start and end addresses) with the given descriptor as a root.

Inside the Nursery

Objects are initially allocated in a nursery using a fast bump-pointer technique. When the nursery is full we start a nursery collection: this is performed with a copying GC.

When the old generation is full, we also perform a collection of the old generation

There are a number of complications over a simple copy collection:

- Pinned objects.

- Large objects (these are too expensive to handle with a garbage collection).

The nursery is a contiguous region of memory where all new objects are allocated, the region is delimited by two global variables nursery_start and nursery_real_end, the nursery_next pointer points to the location where the next object will be allocated.

Implementation Details

Segments of the nursery memory are delimited by the nursery_next and nursery_temp_end. This serves a number of purposes:

- It allows allocations to be done inside fragmented areas of the nursery (due to pinned objects).

- FIXME: scan starts

- Allows for fast, per-thread allocation without any locking to take place.

In the implementation as of May 2006, the nursery_next and nursery_temp_end are global, but we will eventually turn them into per-thread variables to allow thread to do allocations without having to take the GC-lock.

TODO: Pinned objects in the nursery.

Write Barriers

To reduce the time spent on a collection, the collector differentiates between a major collection which will scan the entire heap of allocated objects and a nursery collection which only collects objects in the newer generation. By making this distinction the runtime reduces the time spent during collection as it will focus its attention on the nursery as opposed to the whole heap.

But for this to work we need to keep track of any references from the old generation pointing to the new generation. There are two ways in which an object in an older generation might point to objects in the newer generation:

- During code execution when a field is set.

- During the copy phase, when an object that might contain a pointer to the new generation is moved to the old generation.

To do this, Mono implements write-barriers. These are little bits of code that are injected by the JIT whose job is to update a structure that keeps track of these changes.

Mono supports two data structures to keep track of this, card tables (the default on most platforms) and remembered sets (this can be configured by setting the wbarrier flag to cardtable or remset in the MONO_GC_PARAMS variable)

When using remebered sets, the JIT uses a per-thread RememberedSet which is stored in the thread-local remembered_set variable, this is done in cooperation with the JIT which instruments all object stores to call some helper routines in the GC that implement the write barrier, the mono_gc_wbarrier_* functions.

The second kind, the ones generated during object copying, are tracked in the global RememberedSet, in the global_remset variable.

The per-thread remembered set is maintained as code executes and by being a per-thread variable, it is lock-free. The global remembered set is maintained when the world is stopped and the GC lock is held.

When we collect the whole heap the root set is basically thread stacks and static fields.

When we collect the young generation we use the remembered sets as roots so that objects in the young generation that are referenced from objects in the old one are kept alive.

Card tables barriers are faster, but are less precise and are only supported for the mark and sweep colletor on 32 bit platforms

Flagging Objects

During the copying phase the collector needs to track some information efficiently: whether a given object is pinned, and whether a given object has been copied to an older generation (forwarded).

To avoid creating new lists or scanning arrays, during the collection the two lower bits of the vtable of the object are used to store this information. Every object in Mono is represented by the following structure:

typedef struct {

MonoVTable *vtable;

MonoThreadsSync *synchronisation;

} MonoObject;

As the vtable is a pointer, it is guaranteed to always be aligned to 4-bytes the two lower bits of the vtable are always zero. During the collection the collector uses these two bits to store two flags: PINNED and FORWARDED. When the collection is complete these bits are cleared to restore the original value of the vtable pointer.

Conservative Scanning

Before the actual collection takes place, it is important to find all the objects that can not be moved (the pinned objects), there are two kinds of pinned objects, those that were explicitly pinned by the runtime or the programmer (using the fixed expression or object references that are passed to unmanaged code with P/Invoke) and those which are identified by a conservative scan of the stacks and thread registers.

The thread stacks and the registers must be conservatively scanned, which means that the memory regions are scanned for pointer-sized patterns that might point to objects allocated and the heap, and if such a match is found, the object is considered to be pinned.

This is necessary since Mono does not currently track object usage on the stack and the current registers of a routine. This means that Mono does not know which values on the stack are actual object references, nor which values on the registers at the point that a thread was stopped points to objects. Since the GC would be unable to make the distinction between a reference to an object and a variable which holds a value that just happens to look like a pointer, the GC must err on the side of safety and assume that the object is pinned. By assuming that the object is pinned, the collector does not move these objects, nor does it have to update the stack contents and the register values to contain this information.

A future version of Mono might track as code is generated where object references are tracked on the registers and where they are stored on the stack. Only then it would be possible to scan the thread stack and registers precisely instead of conservatively.

At the implementation level, a pinnect object is merely an object that the copying phase of the collector will ignore and will not move to the older generation.

To do this efficiently the collector flags these objects with the pinned flag on its vtable.

The pinning process has two stages:

- Identifying pinned objects explicit and implicit (conservative scanning).

- Flagging the objects individually as pinned.

Once the objects have been flagged as pinned, the copying collection can begin.

The identification of pinned objects is done by the pin_from_roots function. This functions scans all of the pinned locations: the registered pinned roots (see “Pinned Objects”) as well as all of the thread stacks, which at this point also contain the contents of the registers in use in each thread.

The routine constructs a list of all pinned objects in the pin_queue array. The contents of this array are then optimized by the optimize_pin_queue which sorts the contents and removes any duplicates from it.

Once the list of unique addresses has been created, the collector has to flag the object before the collection can start. This is done by pin_objects_from_addresses.

pin_object_from_addresses has to cope with one problem, the addresses in the pin_queue do not necessarily point to the beginning of the object, these pointers might very well be pointing somewhere in the middle of the object, so its necessary to map the address in the pin_queue to the object start. Since objects are allocate sequentially in the memory section, it is possible to do this mapping by scanning from the beginning of the memory section, but this could be very time consuming.

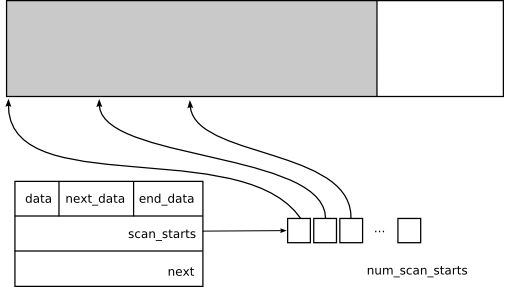

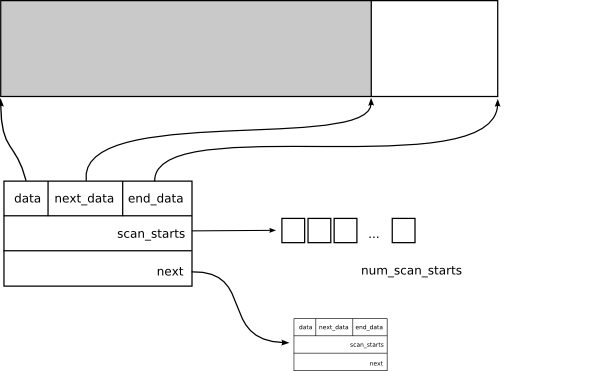

This process is optimized by using the scan_start array of pointers from the GCMemSection:

Every 4k to 8k of objects sequentially allocated an entry in the scan_starts array is allocated. This way we only have to scan between 4096 and 8096 bytes of memory to find the header of the object to pin.

The contents of the scan_starts array is maintained in the mono_gc_alloc_obj and the copy_object functions.

Scanning Objects

TODO: describe scanning.

The compacting collector needs a mechanism to move objects (from the nursery to the old generation for example). When an object is copied, it is important that all references pointing to it are updated to point to the new location.

All objects that have are currently referenced are copied to the older generation, this is done by the copy_object routine which does a bit copy of all the object contents.

Once an object has been copied to its new destination, in the old copy of the object the “forwarded” bit is turned on in the vtable field and the synchronization pointer is updated with the new location of the object. This is safe to do, since the object at this point is no longer in use at the old address.

This information is used to update all the existing references to the object to point to the new location.

Dray Gray Stack

Pinned Objects

The garbage collector also supports “pinned” objects, these are objects that for some reason should not be moved. For example, if an object reference is passed to an unmanaged function through P/Invoke, the object is pinned, as unmanaged code can not cope with objects that move behind its back. Objects are also pinned when developers use the fixed statement in C#, like this:

fixed (MyObject *p = &object){

...

}

Notice that `p’ might point to the beginning of the object, or through pointer manipulation anywhere inside the object or even outside the object, the GC must account for this.

Mono also pins objects when conservatively scanning the thread stacks and the registers (more on this shortly).

Pinned objects also have the potential of fragmenting the heap and they reduce the effectiveness of the GC as these objects become obstacles for the compacting process.

Pinned objects can be registered with the garbage collector by calling the mono_gc_register_root function with a NULL descriptor, which has the following prototype:

mono_gc_register_root (char *start, size_t size, void *descr);

If the descriptor is NULL, the GC will treat the region starting at “start” for “size” bytes as a block of memory that contains pointers to objects. Any objects in that range will be pinned.

A convenience macro is available from C to register a variable as a pinned root, you can use the MONO_GC_REGISTER_ROOT macro to register a variable as a root.

Compacting collectors have some challenges to solve. For instance, when an object is moved, all of the pointers that refer to it must be updated to reflect the new location of the object. Although it is relatively simple to update the pointers in known managed locations, there are some locations that are hard to track: references that might be held on the stack of a thread, or in the registers of a thread.

Today Mono does not track the object references in the thread stacks or in the registers of a thread, instead Mono conservatively scans the thread stacks and the registers for each thread and assumes that anything in those spaces that might be a pointer into the GC-controlled heap is a valid pointer into the GC-controlled heap.

This means that the collector treats any object that might be referenced from this areas as a pinned object.

Finalizers

Implementation Details

Low-level Memory Allocation

Memory inside the GC is allocated from two sources:

get_internal_mem(size_t size)get_os_memory(size_t size, int activate)

get_internal_mem is used for small allocations, and is very similar to malloc, but memory is obtained from the internal chunks created by the GC.

For large allocations, memory is obtained from the operating system using the get_os_memory. The returned blocks of memory returned from get_os_memory are aligned to the operating system page alignment. get_os_memory allocates memory directly from the operating system circumventing the C runtime malloc-based system and it is implemented in Unix using mmap(2) over /dev/zero.

GCMemSections

Major blocks of memory managed by the GC are tracked in the GCMemSection structure. This structure tracks the memory allocated from the operating system and objects are allocated back-to-back in the chunk of memory obtained from the operating system.

The structure looks like this:

The grey area represents the pieces of this particular section that have been used. The next field is used to keep track of all the GCMemSection structures allocated in a linked list.

The scan_starts array is used as an optimization to minimize the memory that must be scanned for pinned objects, this is discussed in the Conservative Scanning section.

When a nursery collection happens, the live and movable objects from the nursery are copied into a new GCMemSection.

Large Object Allocation

Note: SGen-GC’s Large Object Allocation strategy is an evolving one. The description in this paragraph reflects the implementation as of Mono 2.12 and will likely change as the GC is tuned to cope with most common usage patterns.

Since moving large objects is an expensive operation, the GC treats any objects above 64k specially (the actual size is MAX_SMALL_OBJ_SIZE, a value defined in the sgen-gc.c file). These objects are allocated using the get_os_memory routine.

These objects do not participate in the copying/compacting process and are not stored in the memory managed by GCMemSection. Instead these objects are managed by a mark and sweep algorithm during a major collection and are kept track in a global list of large objects (in the structure LOSObject and the los_object_list linked list).

When an object has been determined to be unused, the memory is returned to the operating system immediately (this is possible because the memory is allocated using get_os_memory as opposed to the regular malloc from the C runtime).

Fragments

Since sgen supports pinning nursery objects, we cannot use a bump pointer to allocate on it. Instead, at the end of a minor collection, we collect all fragments of free memory in between pinned objects to allocate from them.

So, a fragment is simply a start address and a size that describes a region of memory to which we can bump alloc into. They are organized in a linked list and the mutator tries to alloc from them until none is usable and another collection cycle is triggered.

To balance performance and nursery utilization we sometimes discard fragments that are too small. This is controlled by the SGEN_MAX_NURSERY_WASTE define.

Descriptors

Creating Root Descriptors

To create such a descriptor, the following routine is used:

void *mono_gc_make_descr_from_bitmap (gsize *bitmap, int numbits);

This routine will return a descriptor that encodes the object references as specified in the given bitmap (one bit per pointer). Internally the routine will find the best possible descriptor encoding for the given bitmap, as of this writing the routine will create a bitmap descriptor, provided that the bitmap fits on a pointer, otherwise it will return a ROOT_DESC_CONSERVATIVE descriptor.

The code should eventually support other descriptor encodings like ROOT_DESC_RUN_LEN and ROOT_DESC_LARGE_BITMAP in addition to the two existing ones.

GCVTable

Runtime Interface

The runtime will sometimes need to keep pointers to managed objects. It is important that the GC is aware of them, since it needs to update the pointers when the objects are moved.

There are two data structures that are provided to help: the MonoGHashTable and the MonoMList.

MonoMList

MonoMList is a single linked list that can store references to managed objects. This list is mirrored in the managed world in the internal corlib class System.MonoListItem

MonoGHashTable

Precise Stack Marking

By default SGen scan the stack precisely on most platforms (OSX is a notable exception). You can control whether SGen uses precise or conservative scanning by setting the stack-mark=<code> flag in the <code>MONO_GC_PARAMS variable.

Both Boehm GC, and SGen on OSX scan threads stacks conservatively. This means that they treated every value found on a stack as a potential pointer. This is problematic for several reasons:

- The possibility that some objects remain alive by mistake, because a value which points to them is found on the stack.

- For SGen, objects pointed to by stack values will remain pinned, fragmenting the nursery and hurting collector performance.

- Handling pinning pointers is somewhat slow, requiring a linear search through parts of the nursery.

SGen now has the ability to scan most of a threads stack precisely on Linux. This is done by the creation of GC Maps, which describe which stack locations/registers contain references at every point inside a managed method where a GC could occur. While running the Mono’s corlib test suite the number of pinned objects went from 90k to 45k when using the new Precise Stack Marking.

Currently SGen still needs to scan the native frames conservatively as those could contain pointers to live objects (for example inside internal calls).

Sources

The source code for the stack marking code is in mini/mini-gc.c, it communicates with sgen through a set of callbacks registered during startup.

GC Maps

A GC Map consists of ‘slots’. A slot can describe either a stack slot, or a register. A slot can have three types:

- NOREF - This means the slot doesn’t contain a GC reference, either because it has a type which needs no GC tracking, i.e. ‘int’, or it once contained a GC reference, but the reference is no longer live.

- REF - This mean the slot definitely contains a live object reference.

- PIN - This means that either the slot contains a managed pointer, or we have no information for the slot. This slot will be treated conservatively.

During a GC, there is a set of stack frames on the stack. All but the last frame is guaranteed to be at a call site. To simplify things, we treat the last frame conservatively. This means we only have to create GC Maps for each call site, not for each native offset through a method’s code.

GC Map slots are encoded using 2 bitmaps. The first bitmap is called ‘ref’ and contains a bit at an (x, y) position if the stack slot/register ‘x’ has type REF at the callsite ‘y’. The other bitmap is called ‘pin’, and contains the same info for type PIN. If none of the bits are set at a given (x, y) position, then the slot has type NOREF. There are 2 bitmaps for stack slots, and 2 for registers.

GC Maps can take up a lot of memory, so they are stored in an encoded form, and only decoded during stack marking.

Stack Frames

A frame on a stack consists of stack slots. Currently, we handle the following types of stack slots:

- Slots used by the prolog/epilog. This includes the slot storing the return address, saved registers, padding slots used for aligning the stack etc. The arch specific code in mono_arch_emit_prolog () notifies the GC Map creation code about these slots using internal API calls.

- Slots holding arguments/locals. We have precise type information for these. We do a GC specific liveness pass to determine which of these slots are alive at each call site. There are many subtypes of these slots, i.e. ones holding refs/non refs/byval variables, volatile variables, vtypes, etc. Since stack slots are shared, it is possible for one to hold a REF at one call site, and a NOREF at another.

- Spill slots used by the local register allocator.

- Param area slots which are used for passing arguments to called methods on the stack.

Each frame has a frame pointer register, which is either sp or an arch specific dedicated frame pointer register. All stack slots are stored at positive or negative offsets relative to the frame pointer.

Stack Marking

Stack marking is done in two passes, a conservative pass and a precise pass. This is required because of the way sgen works. The conservative pass does a stack walk using the JIT stack walking infrastructure, and processes slots which have type PIN, while the precise pass processes slots which have type REF. To avoid doing a stack walk twice, information needed by the precise pass is saved during the conservative pass in TLS, and the precise pass uses this information to perform its work.

Registers needs special handling, because register values belonging to the current frame are not saved by the current frame, they are saved by a child frame when it uses the same register. This is handled by keeping track of where each register was last saved during the stack walk, and marking this save location based on the information in the GC Maps. I.e., if the GC Map tells us that %rbx contains a REF in the current frame, we find out where %rbx was saved by a child frame and mark that location precisely.

Some parts of the stack are still scanned conservatively, these include the native frames below the last managed frame, the last managed frame, frames belonging to managed->native transitions, and all native frames above the first managed frame.

Testing

There are some tests for the stack marking code in mini/gc-tests.cs. Stack marking is very hard to test, because a missed reference might not cause a problem since the object pointed to by the reference might be kept pinned by another stack location etc.

Efficiency

The efficiency of the code can be measured by the number of objects pinned during collections. Running mono --stats prints this information:

Number of pinned objects : 2

When running the test suite in Mono’s mscorlib (make check in mono/mcs/class/corlib), the precise stack marking code reduces the number of pinned objects from 96k to 40k. The remaining pinned objects are mostly:

- objects which really need pinning, i.e. ones pointed to by managed pointers etc.

- objects pinned by native code, particularly

MonoInternalThreadobjects andThreadStartdelegates, which are referenced by the thread startup native code.