GUI Toolkits

Picking the Right Toolkit

One of the hardest and most important decision to make when starting a new desktop application is which GUI “toolkit” to choose. The toolkit is the set of API’s that produce the graphical user interface your users will interact with.

There are a number of factors to consider when choosing the toolkit. Different toolkits support different platforms (Linux, Windows, OSX) and have different features such as accessibility, layout engines, and looks.

The two main toolkits offered by Mono are GTK# and Winforms, however there are several other toolkits offered by the community which may suit your needs.

Both GTK# and Winforms, while being cross-platform, have clear roots in their original platforms. Gtk+ (the root of GTK#) began life on the Linux platform, and has since been ported to Windows and OSX. Likewise, Winforms started on Windows, and the Mono project has ported it to run on Linux and OSX. If the majority of your users will be on one platform, likely the best choice will be the toolkit native to that platform. Although steps can be taken to make your application blend on all platforms, the native toolkit will probably do the best on each platform, and will feel familiar to the majority of your users. If you do not have a platform preference, your toolkit choice will have to rely on other factors.

Toolkits

Gtk#

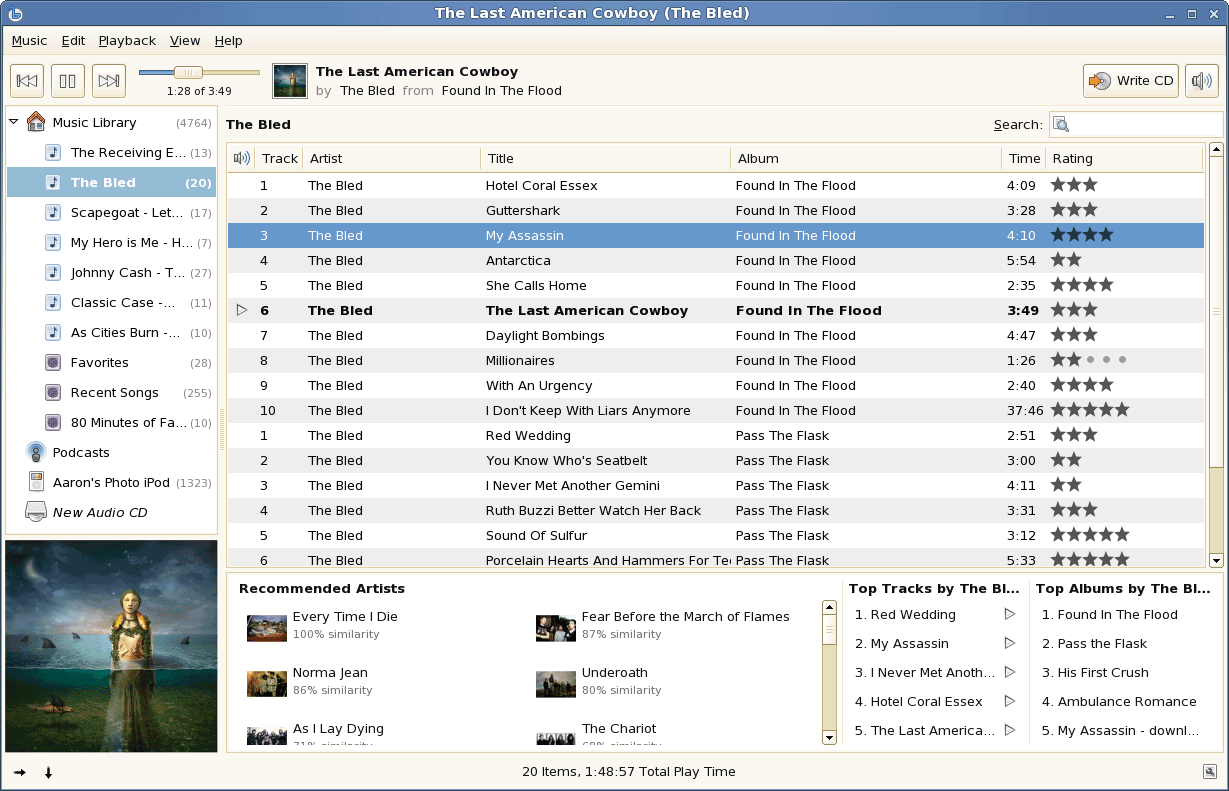

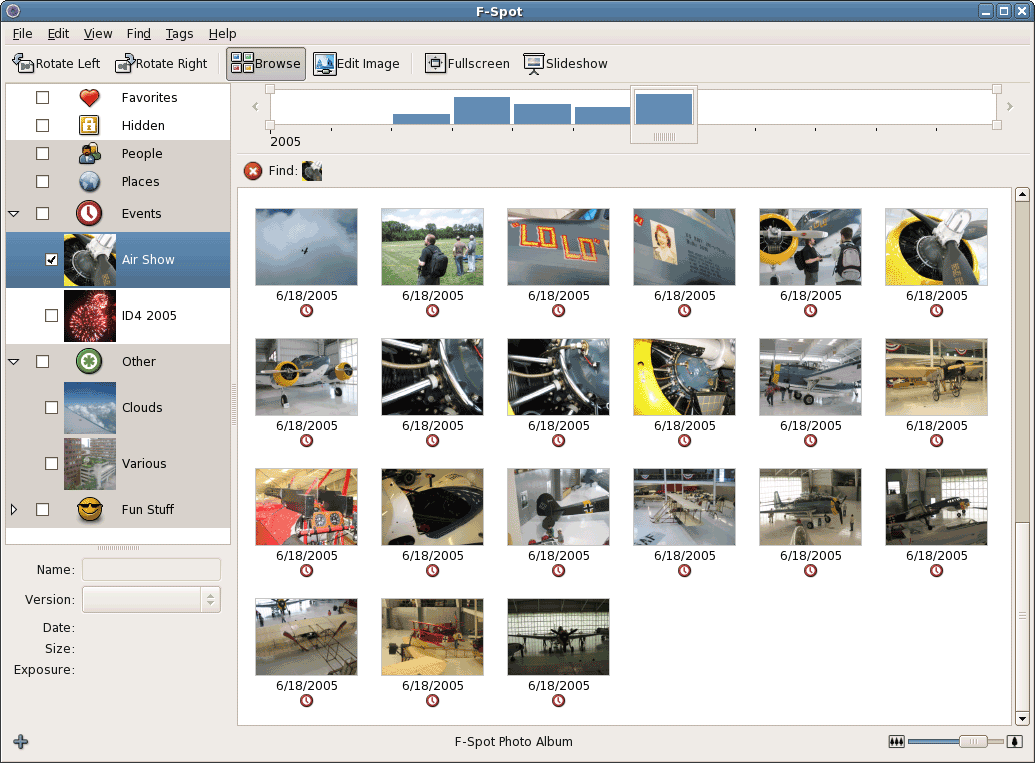

Banshee, a GTK# app

F-Spot, a GTK# app

Homepage: GtkSharp

GTK# is a .NET binding for the Gtk+ toolkit. The toolkit is written in C for speed and compatibility, while the GTK# binding provides an easy to use, object oriented API for managed use. It is in active development by the Mono project, and there are various real-world applications available that use it (Banshee, F-Spot, Beagle, MonoDevelop).

In general, GTK# applications are written using MonoDevelop, which provides a visual designer for creating GTK# GUIs.

Platforms: Unix, Windows, OSX

Pros:

- Good support for accessibility through its Gtk+ heritage.

- Layout engine ideal for handling internationalized environments, and adapts to font-size without breaking applications.

- Applications integrate with the Gnome Desktop.

- API is familiar to Gtk+ developers.

- Large Gtk+ community.

- A Win32 port is available, with native look on Windows XP.

- The API is fairly stable at this point, and syntactic sugar is being added to improve it.

- Unicode support is exceptional.

Cons:

- Gtk+ apps run like foreign applications on MacOS X.

- Incomplete documentation.

MonoMac

Homepage: MonoMac

MonoMac is aimed at .Net/Mono developers that want to allow their users to have a native Mac OS X application experience. MonoMac allows developers to access the whole range of MacOS X APIs from C#, it is not limited to the AppKit GUI APIs.

The MonoMac APIs replaced the old CocoaSharp binding, which is now deprecated.

Platforms: OSX

Pros:

- Native look and feel on MacOS X.

- Substrate is well documented.

Cons:

- Not portable outside of MacOS X.

Windows.Forms

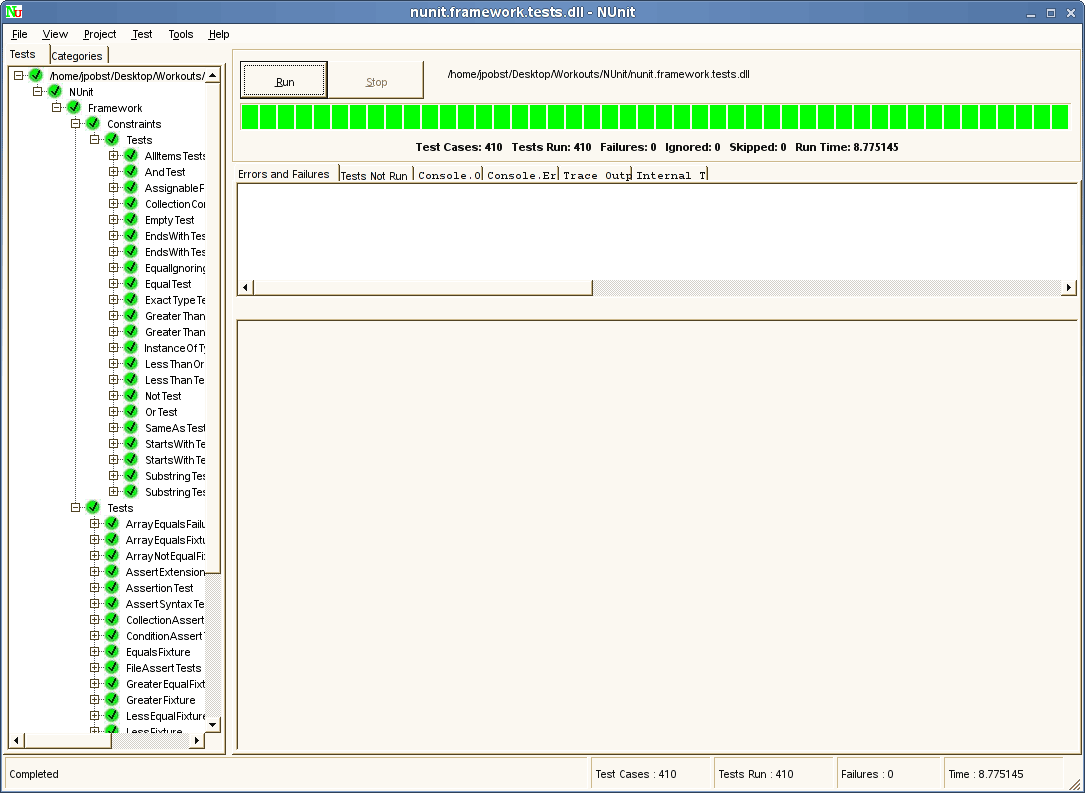

NUnit, a Winforms app

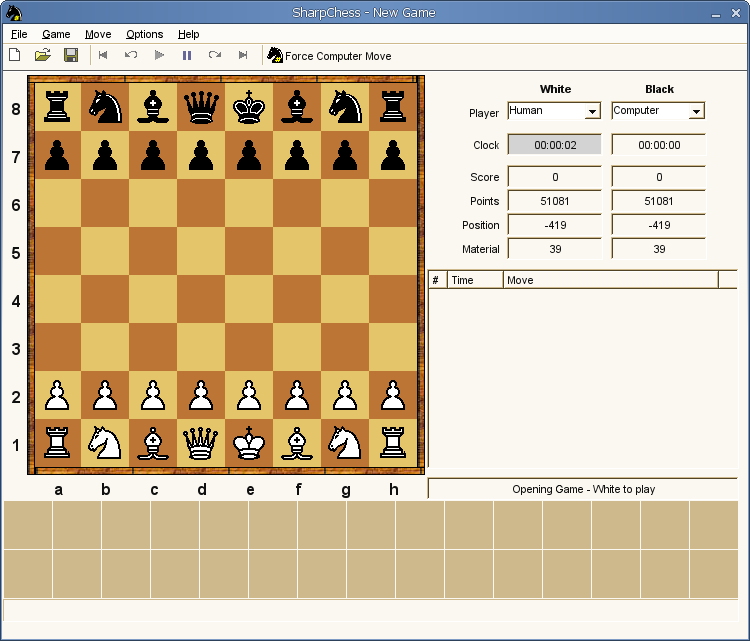

SharpChess, a Winforms app

Homepage: Winforms

Windows.Forms is a binding developed by Microsoft to the Win32 toolkit. As a popular toolkit used by millions of Windows developers (especially for internal enterprise applications), the Mono project decided to produce a compatible implementation (Winforms) to allow these developers to easily port their applications to run on Linux and other Mono platforms.

Whereas the .Net implementation is a binding to the Win32 toolkit, the Mono implementation is written in C# to allow it to work on multiple platforms. Most of the Windows.Forms API will work on Mono, however some applications (and especially third party controls) occasionally bypass the API and P/Invoke straight to the Win32 API. These calls will likely have to changed to work on Mono.

In general, Winforms applications are written using Microsoft’s Visual Studio or SharpDevelop, which both provide a visual designer for creating Winforms GUIs.

Platforms: Windows, Unix, OSX

Pros:

- Extensive documentation exists for it (books, tutorials, online documents).

- Large community of active developers.

- Easiest route to port an existing Windows.Forms application.

Cons:

- Internationalization can be tricky with fixed layouts.

- Looks alien on non-Windows platforms.

- Code that calls the Win32 API is not portable.

Qyoto

Homepage: Qyoto

The Qyoto/Kimono languages bindings allow C# and any other .NET language to be used to write Qt/KDE programs. The bindings are autogenerated directly from the Qt/KDE headers, greatly reducing the maintenance effort. KDE doxygen comments are automatically converted to the xml based C# style of comment format. Substrate is well documented and supported. Qyoto 4.0 got nice Documentation too.

Platforms: Unix, Windows, OSX

On Debian/Ubuntu, it can be installed by installing the ‘qyoto-dev’ package.

Qt4Dotnet

Homepage: Qt4Dotnet

This is a port of the QtJambi java bindings to .net using IKVM.

wxNet

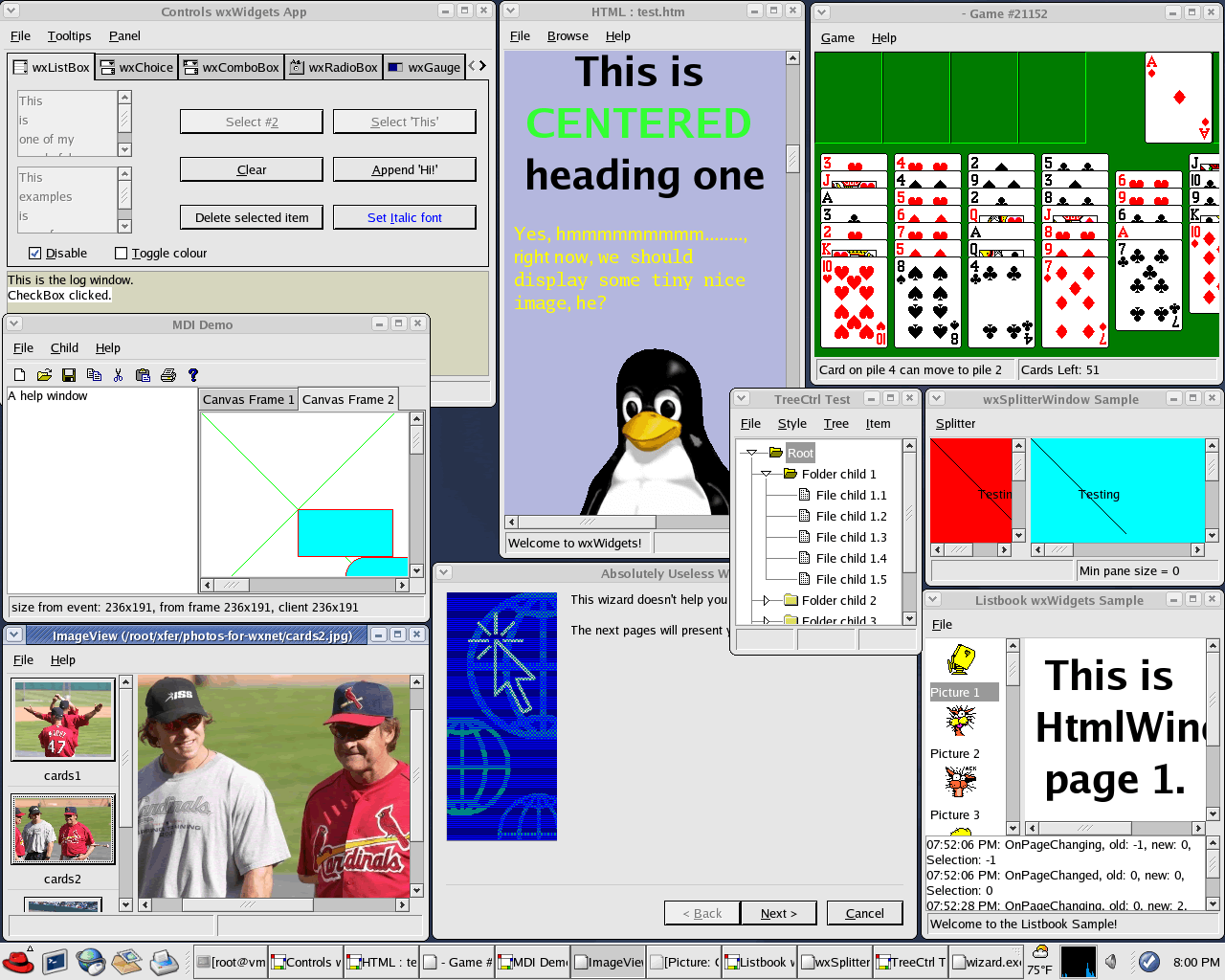

wx# Sample

Homepage: http://wxnet.sourceforge.net/

wxNet is a .NET binding for the wxWindows cross-platform toolkit.

Platforms: Windows, Linux, OSX

Pros:

- Native look and feel on each platform.

- Substrate (wxWindows) is well documented, .NET binding lacks documentation.

Cons:

- Binding to non-supported extra widgets is hard.

- Custom-authored widgets look and feel is not preserved across platforms.

- Common denominator subset API problem.

Dead efforts

There are a couple of Dead Toolkits that have been developed in the past.

Alternative Implementation Approaches

If your application is designed to be a long-running application and you have the extra resources to spare you might want to consider creating multiple operating system specific user interfaces, one for each major platform.

The idea is that you must split your application in parts:

- Core: this contains the hearth of your application, your logic, your business process.

- Front-end: this contains the UI front-ends for each platform.

You could even take this one step further and in addition to have a front-end per platform, you could even make a Web frontend if the Core is suitable for it.

The downside is that you have to write the code more than once, but the upside is that your application will look native on each platform.

Although some toolkits support themes, theme engines and try to mimic the host operating system, making an application truly operating system specific goes beyond the basic look.

There are a number of examples:

- The order of buttons in dialog boxes tends to be different between Windows and MacOS/Gnome.

- Dialog Box Layout: this tends to change across operating systems.

- Configuration options: these tend to be radically different across different operating systems.

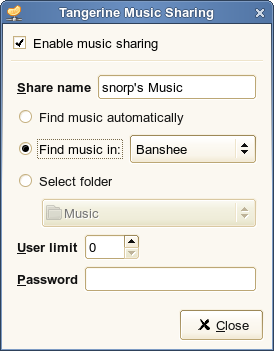

As an example, consider the UI for Tangerine an application used to stream music over DAAP. Tangerine has a core engine and three user interfaces, one for each major operating system:

On Windows:

On Linux with Gnome:

On MacOS X: